by Aly Sizer

This week ITV viewers have been catching up with a group of people who represent half a century of social change in England – the cast of the Up documentary series, which has followed these 14 people since 1964.

The aim of the series is to test the validity of the old Jesuit motto, “Give me a child until he is seven and I will give you the man”. And here at UCL’s CeLSIUS centre we’re well placed to judge whether the pen portraits in these films really do represent life in Britain over this period.

We support the use of the ONS Longitudinal Study (LS), which is based on a 1% sample of Census returns since 1971 and linked to other life events such as births, emigrations and cancer registrations. The study now includes records for more than a million individuals and provides the basis for a rich and detailed analysis of our social geography in recent decades.

So, how fair a representation of society are the programmes? And could the participants’ pathways through life really have been predicted back in 1964? We took a delve into the data to find out. And, by and large, we found that this group did represent their generation.

Out of the original 14 in the TV programmes, three could be said to have diverged from what might have been expected of them, given their childhood social class.

Nick, raised on a small farm in North Yorkshire, became a professor. Lynn, brought up in the East End of London, became a librarian. Tony, who went to the same primary school as Lynn, did skilled work as a cabbie, had some success as an actor and at one point had a holiday home in Spain.

In all, five participants – four men and one woman –started out in a high social class, and all stayed there. All four men went to university and gained professional or managerial jobs. The woman, Suzy, dropped out of school at 16 but later married a solicitor and was able to stay at home to raise a family.

Two participants started out in middle class homes. Both went to university but one, Neil, started dropped out and became homeless for a time. But he later became a councillor, stood for Parliament and completed an Open University degree in his forties.

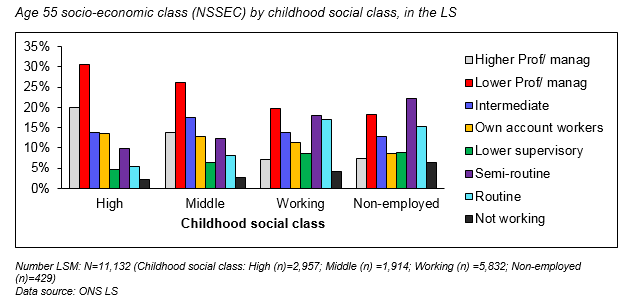

Similarly, we found that LS members who grew up in a high social class households had advantages over those who grew up in working class households. Higher percentages of LS members from a high social class in childhood had professional, managerial or technical jobs as adults. Conversely, LS members from working-class families were more likely to be in a disadvantaged social class in adulthood.

In our analysis, we also took the occupations that the Up-series participants held and then we looked at the childhood circumstances of LS members who had the same jobs. The LS occupies a unique position in being able to do this, since its size means that, for the most part, there are sufficient numbers to look at specific occupations. We weren’t able to get large enough samples of librarians or councillors, but for all the other Up participants we could do this.

Our findings showed even Nick the professor wasn’t really that unusual – more than a quarter of professors in our sample had come from working-class backgrounds and his journey from a small village school to an American university wasn’t exceptional.

So, was the programme’s premise correct? By and large, it shows that the Up-series participants did have similar early life experiences to LS members going on to hold similar occupations.

Of course, the TV series was based on a very small sample and our comparable cohort gave us a much more nuanced understanding of social change, and how this has changed over time. We can see from our study that social mobility was more common than the series might suggest – the expansion of women’s employment was one of the reasons for this, but there were only four women in the programmes and so this was largely missed.

But by and large we could take a sample of children at age seven and see the men and women they might become. So in broad terms the Jesuits – and the programmes – had it just about right.

Aly Sizer works with CeLSIUS. She has just completed her PhD (funded by the ESRC). Her research interests include ageing, the social determinants of health and life course epidemiology, and she is also interested in data visualisation.

Aly Sizer works with CeLSIUS. She has just completed her PhD (funded by the ESRC). Her research interests include ageing, the social determinants of health and life course epidemiology, and she is also interested in data visualisation.

CeLSIUS is one of the services funded by the ESRC Census Programme and as such its services are provided free of charge to staff and students of UK academic institutions. You can follow CeLSUIS on Twitter at @celsiusnews.